What Is Light Flicker, Really?

Light flicker, technically called Temporal Light Modulation (TLM), is the rapid fluctuation of light intensity over time. Despite what the name suggests, you don't always see it—but your brain is processing it regardless.

The Four Faces of Flicker

This is the obvious kind—the light appears to pulse or strobe. Most people consciously perceive this below 60-80 Hz. Effects include immediate eyestrain, disorientation, nausea, and in extreme cases, seizures. The danger zone is 3-70 Hz (anything less than 3 Hz is usually fine).[1]

Here's where it gets insidious: Your retina can resolve fluctuations up to 200 Hz, and this information gets transmitted to your brain. You don't consciously perceive the flicker, but your visual cortex is working overtime to process it. This can contribute to chronic headaches, malaise, and impaired visual performance. (Note: The evidence in this range is more mixed)

At these higher frequencies, flicker creates perceptual distortions: moving objects appear as a series of still images (stroboscopic effect), or you see multiple "phantom" images during rapid eye movements. Most can perceive these effects at up to 2 kHz, but there are some reports of people seeing them even above 10 kHz

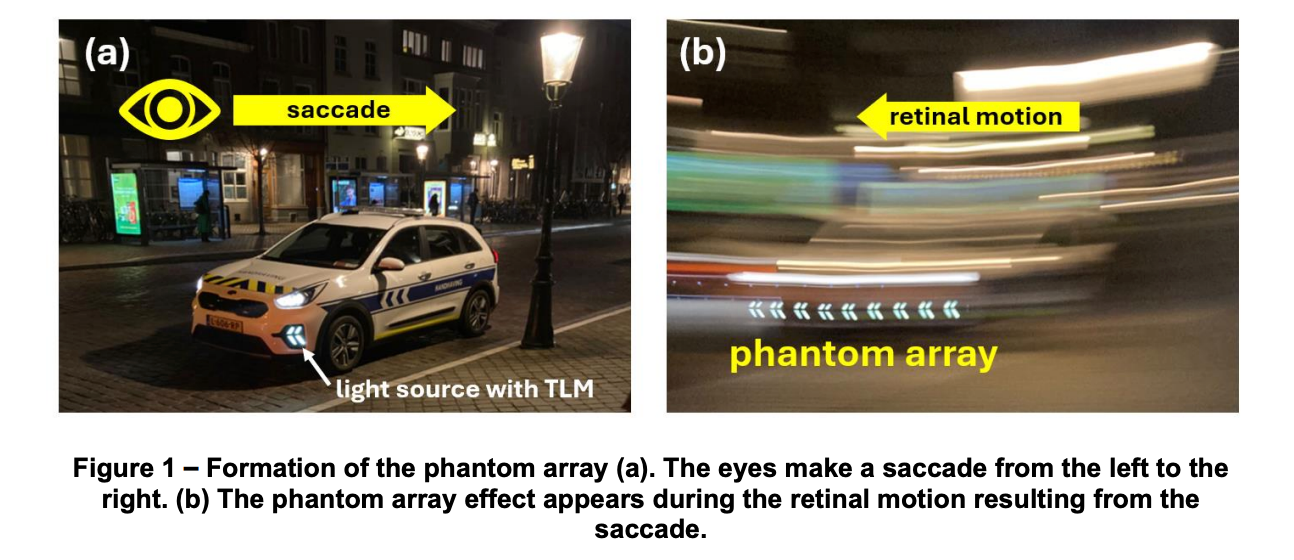

In this regime, the main issue is eye movements. During a quick saccade across a modulated light, your brain stitches together snapshots taken at different phases of the waveform. The result is a dotted trail or “comb” of repeated images: the phantom array. This can remain visible for very sensitive observers even when the frequency is in the several-kilohertz range.[16]

The Four Faces of Flicker: Different frequency bands are dominated by different temporal artifacts—visible flicker, invisible low-frequency strain, stroboscopic distortion, and phantom array tails at very high frequencies. Higher than 2 kHz is better, but it is not automatically “safe” for everyone.

The Three Numbers That Matter

To understand whether a light is likely to be comfortable or harmful, three engineering parameters matter most:

1. Frequency (Hz) – How Fast It Flickers

Frequency is how many times per second the light cycles on and off. Most AC-powered lights flicker at 100–120 Hz because the light output follows the rectified power waveform.

Rule of thumb: Higher is better, but even into the kHz range you can still get phantom arrays if other parameters are bad.

2. Modulation Depth (%) – How Deep the Flicker Goes

Modulation depth (often reported as Percent Flicker) measures how much the brightness varies in each cycle.

Modulation (%) = 100 × [(Lmax − Lmin) / (Lmax + Lmin)]

Where Lmax is maximum brightness and Lmin is minimum brightness in one cycle.

- 0% modulation = perfectly constant light (ideal).

- 100% modulation = light goes fully on → fully off (worst case).

Aim for: ≤5–10% modulation whenever possible. Above ~30% is a red flag, especially below 1 kHz.

Modulation Depth Matters: Low modulation (teal) produces gentle ripples in brightness. High modulation (red) is effectively strobing on/off—much harsher on the nervous system.

3. Duty Cycle & Flicker Index – How the Bright and Dark Parts Are Arranged

Two waveforms can have the same frequency and the same modulation depth, but feel very different to the brain depending on how the “on” and “off” parts are arranged.

- Duty cycle (for PWM) is the fraction of time the light is ON in each cycle.

- Flicker Index measures how “top-heavy” the waveform is—how much area is above the average line vs below it over one cycle.

For an ideal PWM signal (0% when off, 100% when on):

- At 50% duty cycle, the light is on half the time and off half the time → Flicker Index is about 0.50.

- At 10% duty cycle, it’s mostly dark with short bright flashes → Flicker Index ~ 0.90 (extremely harsh).

- At 90% duty cycle, it’s mostly bright with short off gaps → Flicker Index ~ 0.10 (less harsh).

Duty Cycle vs Flicker Index (Ideal PWM): The lower the duty cycle (short bright flashes in a dark background), the higher the Flicker Index and the harsher the waveform, even if frequency and percent flicker are the same.

The Engineering Behind the Problem

Here's the paradox: LEDs are the most efficient lighting technology ever invented, yet many LED products on the market create worse flicker than technologies from the 1950s. Why?

LEDs Respond Instantly to Power Changes

Unlike older technologies, LEDs are semiconductor devices that respond to current changes in nanoseconds. Any ripple or modulation in the power supply is immediately translated into brightness flicker. There’s no “thermal inertia” to smooth it out like there was with incandescent filaments.

Cheap Drivers = Bad Flicker

LEDs require direct current (DC) to produce steady light, but your wall outlet provides alternating current (AC). The driver circuit converts AC to DC, and this is where the problem originates.

Inexpensive drivers leave a big 100/120 Hz ripple and often use mid-frequency PWM for dimming. The result is high modulation, ugly waveforms, and a perfect recipe for temporal light artifacts at multiple frequency bands.

How Driver Quality Affects Flicker

PWM Dimming Makes It Worse

The most common dimming method is Pulse-Width Modulation (PWM). Instead of reducing current gradually (analog dimming), PWM rapidly switches the LED on and off at full power—often hundreds or thousands of times per second.

While efficient and cheap, PWM inherently creates 100% modulation depth with a harsh square-wave pattern. This is the single worst flicker profile for human neurology.[3]

PWM vs. Analog Dimming: PWM (top) rapidly switches between full-on and off states—efficient but neurologically harsh. Analog dimming (bottom) gradually reduces current for smooth, low-modulation output.

The Neurological Pathway from Light to Pain – How Flicker Affects the Brain and Body

Flicker is not just a visual annoyance. It’s a neurological stimulus that can affect the brain, eyes, and even the autonomic nervous system.

Short-Term Symptoms

- Headaches or migraine attacks

- Eye strain and visual fatigue

- Difficulty focusing or reading

- Dizziness or nausea

- Sensation of “pressure” behind the eyes

Longer-Term Concerns

- Chronic migraine sensitization

- Reduced visual comfort at work or school

- Lower tolerance for screen time or bright environments

- Potential interactions with sleep and mood when combined with blue-heavy spectra

The Hyperexcitable Migraine Brain

People who suffer from migraines (~12-15% of the population) have brains in a state of cortical hyperexcitability.[4] Their visual cortex neurons have a lower threshold for firing and respond excessively to sensory stimuli.

Neuroimaging studies (EEG, fMRI, MEG) consistently show that when migraineurs are exposed to visual stimuli like flicker, their brains exhibit abnormally large and widespread cortical activation compared to controls.[4] This hyperactivity isn't limited to the primary visual cortex—it spreads to higher-order visual areas and even adjacent brain regions.[6]

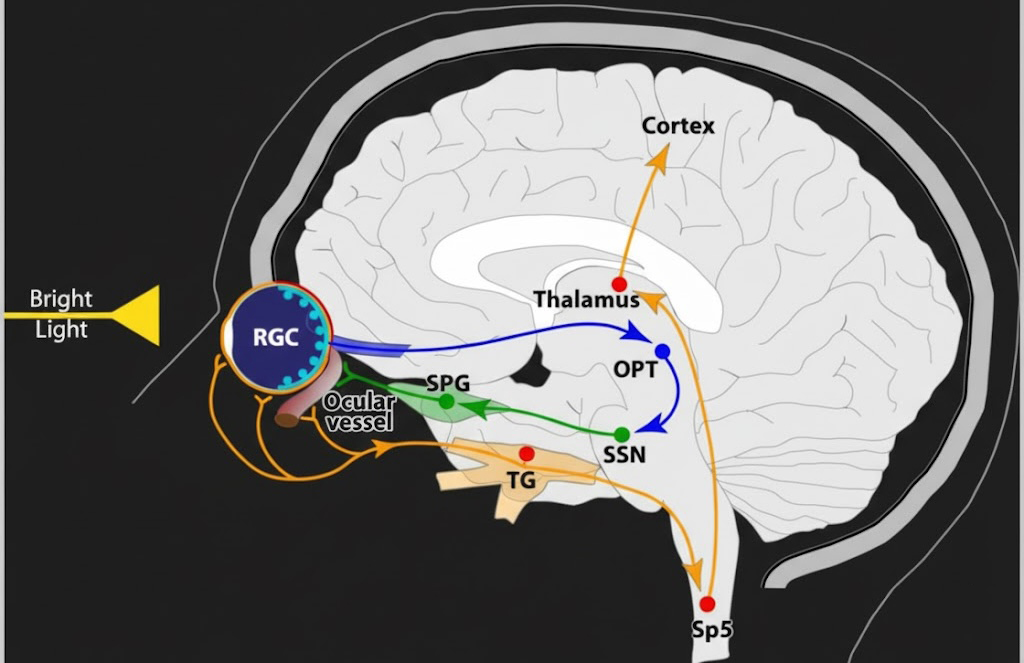

The Vision-Pain Connection

There's a direct anatomical link between your visual system and pain pathways. Research has identified a subcortical pathway where signals from the retina converge in the thalamus with neurons from the trigeminovascular system—the very network responsible for migraine pain.[7]

In healthy people, the visual cortex normally sends inhibitory signals to dampen pain perception. But in migraineurs, this regulatory system is dysfunctional. When the visual cortex becomes massively over-activated by flicker, instead of inhibiting pain, the signal "leaks" across this compromised gateway and activates pain networks.[6][8]

Why Flicker Is Particularly "Unnatural"

The human visual system evolved to efficiently process natural environments. Natural scenes have specific statistical properties—their temporal frequency content follows a 1/f power law (lower frequencies dominate).[3]

Studies show that visual discomfort increases when light patterns deviate from these natural statistics. Flicker—especially the sharp, repetitive square waves from PWM—violates the brain's predictive models of the visual world. This creates a larger "prediction error" that requires excessive neural resources to process.[3]

For the general population, this inefficient processing leads to gradual eyestrain and fatigue. For the hyperexcitable migraine brain, it's enough to trigger a full attack.

A Spectrum of Vulnerability

Flicker doesn't affect everyone equally. There's a clear spectrum from mild annoyance to debilitating neurological events.

Impact: Chronic, cumulative effects

- Eyestrain and visual fatigue

- Non-specific headaches

- Blurred or double vision

- Difficulty concentrating

- General malaise

The Evidence: Replacing 100 Hz fluorescent lights with high-frequency electronic ballasts cut headaches and eyestrain in half in office workers.[1] This proves the 100 Hz flicker was responsible for doubling the baseline headache rate.

Impact: Acute, specific trigger

- 80-90% report photophobia (light sensitivity)[5]

- Lowered aversion thresholds—flicker becomes unbearable at lower intensities[5]

- 10 Hz flicker is highly sensitive trigger[5]

- Flicker can directly precipitate migraine attacks

Case Study: A patient's migraines were reliably triggered by his 60 Hz computer monitor. Changing the refresh rate to 75 Hz completely eliminated the headaches.[10]

Photosensitive Epilepsy: The Extreme End

Approximately 1 in 4,000 people have photosensitive epilepsy (PSE), where flickering lights can trigger seizures. The danger zone is 15-20 Hz, with risk extending from 3-70 Hz.[11]

The parallels with migraine are striking: both involve hyperexcitable neuronal networks in the visual cortex, both respond to similar frequency ranges, and headaches are a common comorbidity in PSE.[11]

Comparing Lighting Technologies: A Historical Perspective

Understanding how different light sources produce flicker helps explain why some are well-tolerated and others are problematic.

| Technology | Frequency | Modulation | Waveform | Tolerance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incandescent | 100/120 Hz | <20% | Sine-like | ✓ High |

| Fluorescent (Magnetic) | 100/120 Hz | ~35% | Non-sine | ✗ Low |

| Fluorescent (Electronic) | >20,000 Hz | <1% | Near-constant | ✓ Very High |

| LED (Cheap Driver) | 100/120 Hz | >50% | Non-sine | ~ Moderate |

| LED (PWM Dimmed) | 120-2000+ Hz | 100% | Square | ✗ Very Low |

| LED (Quality DC Driver) | N/A | <1% | Near-constant | ✓ Very High |

Why Incandescents Are Well-Tolerated

Traditional incandescent bulbs flicker at 100/120 Hz like everything else on AC power, but they're remarkably comfortable. The key is thermal persistence: the tungsten filament doesn't cool down completely during brief AC zero-crossings. This acts as a natural buffer, resulting in low modulation (~10-20%) with a smooth waveform.[12]

The Fluorescent Success Story (That Was Abandoned)

Old magnetic-ballast fluorescents were notorious for causing headaches—they had harsh 100 Hz flicker with ~35% modulation.[1] But modern electronic-ballast fluorescents solved this by operating at >20 kHz, where the phosphor persistence smooths the output to near-constant light.

This was a successful technological solution to the flicker problem. Unfortunately, in the rush to LED adoption, many manufacturers abandoned this hard-won knowledge and reverted to cheap, flickering designs.

Standards: What IEEE 1789 Actually Says

The most commonly cited standard for flicker safety is IEEE 1789-2015. It defines two main regions:

- No Observable Effect Level (NOEL): Very conservative. If you stay below this line, flicker-related health risks are considered negligible for almost everyone.

- Low-Risk Level: Less conservative. Above this line, the risk of adverse effects increases and becomes harder to justify, especially for sensitive populations.

- The problem: Less conservative. Above this line, the risk of adverse effects increases and becomes harder to justify, especially for sensitive populations.

IEEE 1789 “Risk Zones”: At lower frequencies, allowable modulation is extremely small. As frequency increases, the standard allows more modulation—but from a comfort and migraine perspective, less is still better across the whole range.

The Math Behind the Recommendations

IEEE 1789 provides frequency-dependent limits on modulation depth:

- <90 Hz: Max modulation = Frequency × 0.025

- 90-1250 Hz: Max modulation = Frequency × 0.08

- >1250 Hz: No restriction (risk negligible)

Practical Limits for Common Frequencies

| Frequency (Hz) | Max Modulation (%) for Low Risk |

|---|---|

| 50 | 1.25% |

| 100 | 8.0% |

| 120 | 9.6% |

| 400 | 32.0% |

| 1000 | 80.0% |

| 1250+ | 100% (no limit) |

The Phantom Array Effect: High-Frequency Flicker You See Only When You Move

Most flicker guides focus on low-frequency modulation that you see even when your eyes are still. But LEDs can create a second, very different problem at much higher frequencies—even at 1–20 kHz. This is the Phantom Array Effect (PAE).[13]

What Is the Phantom Array Effect?

When you move your eyes quickly across a light source (a saccade), your visual system takes a rapid series of snapshots as the light turns on and off. If the light is being pulsed by PWM or a choppy driver, each snapshot lands at a different point in space. Your brain stitches them together and you see a:

Instead of a single clean light, you see a dotted trail or comb of repeated images across your field of view. That dotted trail is the phantom array.

Key properties:

- You don’t see it when your eyes are still – only during eye movements or when the light moves.

- It’s strongest for rectangular/PWM waveforms with high modulation.

- It remains visible for some people at frequencies well above 10–15 kHz, even though all other artifacts might be gone.

- Subjective reports link strong PAE to headaches, nausea, and visual discomfort in sensitive users. [14]

PAVM – Phantom Array Visibility Measure

Researchers at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory introduced a metric called PAVM (Phantom Array Visibility Measure) to quantify how visible the phantom array is under defined conditions.[13] In short:

- They start from the time-domain waveform of the light.

- Decompose it into frequency components (Fourier spectrum).

- Weight each component by a human sensitivity curve for phantom arrays across frequency.

- Combine components using a Minkowski summation (exponent ≈ 2.1) to reflect perceptual additivity.

The scale is set so that:

- PAVM = 1 → about 50% of observers see the phantom array at threshold.

- PAVM > 1 → phantom arrays are clearly visible for most people.

- PAVM < 1 → phantom arrays are typically weak or absent for most observers.

Frequency Sensitivity of PAE: Sensitivity peaks around ~600–700 Hz but extends into the multi-kilohertz range, especially for rectangular waveforms.

PAH – A Practical Phantom Array Heuristic (From Real-World Metrics)

In an ideal world we’d always have the full waveform and compute PAVM directly. In practice, many meters and datasheets only give you:

- Frequency (Hz)

- Percent Flicker (%)

- Flicker Index

- SVM (Stroboscopic Visibility Measure)

To still rank real products by phantom-array risk, I came up with something I call the Phantom Array Heuristic (PAH)—a single-number metric you can compute from those four values. Conceptually, PAH is built to behave similarly to PAVM, using a weighted Minkowski combination of four components:[13][14]

PAH = [ (wf · Sf)p + (wm · Sm)p + (wi · Si)p + (ws · Ss)p ]1/p

where:

- p ≈ 2.1 (same Minkowski exponent family as PAVM)

- Sf = frequency sensitivity term (peaks near ~700 Hz, tapers down below ~200 Hz and above ~2–4 kHz)

- Sm = modulation term (Percent Flicker normalized to [0,1])

- Si = waveform-shape term (Flicker Index normalized, emphasizing PWM-like asymmetry)

- Ss = stroboscopic/high-frequency artifact term (based on SVM)

- wf, wm, wi, ws are weights chosen so PAH ≈ 1 matches “clear phantom array visibility” in your dataset.

In code, this looks roughly like:

// Pseudocode (not run on this page)

Sf = frequency_weight(freq_hz) // peaked around 600–800 Hz

Sm = clamp(percent_flicker / 100, 0, 1)

Si = clamp(flicker_index / 0.6, 0, 1) // assume FI ≈ 0.6 ~ very harsh PWM

Ss = clamp(SVM / 2.0, 0, 1) // SVM ≈ 1–2 is clearly visible

p = 2.1

PAH = ((wf*Math.pow(Sf, p) +

wm*Math.pow(Sm, p) +

wi*Math.pow(Si, p) +

ws*Math.pow(Ss, p)) )**(1/p)

You then interpret PAH on a scale similar to PAVM:

| PAH Range | Interpretation | Expected Phantom Array Visibility |

|---|---|---|

| < 0.3 | Very Low Risk | Phantom arrays rarely visible, even to very sensitive users. |

| 0.3 – 0.5 | Low Risk | Occasional faint phantom trails for sensitive users during large eye movements. |

| 0.5 – 0.7 | Moderate Risk | Phantom arrays visible for a substantial minority of people; may be annoying in some contexts. |

| 0.7 – 1.0 | High Risk | Most people will see clear phantom arrays; likely to be uncomfortable in everyday use. |

| > 1.0 | Very High Risk | Strong, obvious phantom streaks; inappropriate for health-focused or visually demanding environments. |

How to Test Your Own Lights

You can get a surprisingly good sense of flicker risk with just a smartphone and a little technique. Dedicated flicker meters give the most accurate picture, but even DIY methods can catch the worst offenders.

Open your phone's camera app and point it at the light source. Look at the screen—if you see dark bands rolling across the image, that's visible flicker. Most effective with 100-120 Hz flicker.

Limitation: Cameras have their own refresh rates, so absence of bands doesn't guarantee flicker-free operation.

Record the light in slow-motion mode (120+ fps). Play it back—if the light pulses or strobes in the video, it has significant flicker. This reveals high-frequency flicker your eye can't see directly.

Best for: PWM-dimmed LEDs and cheap drivers.

Wave your hand rapidly in front of the light source. If you see multiple distinct "afterimages" of your fingers (like a stroboscope effect), the light has problematic flicker.

Result: Smooth blur = good. Multiple separate images = bad flicker.

If you’re serious about avoiding flicker, a dedicated flicker meter is the gold standard. Look for tools that report at least:

- Frequency (Hz)

- Percent Flicker (%)

- Flicker Index

- SVM (Stroboscopic Visibility Measure)

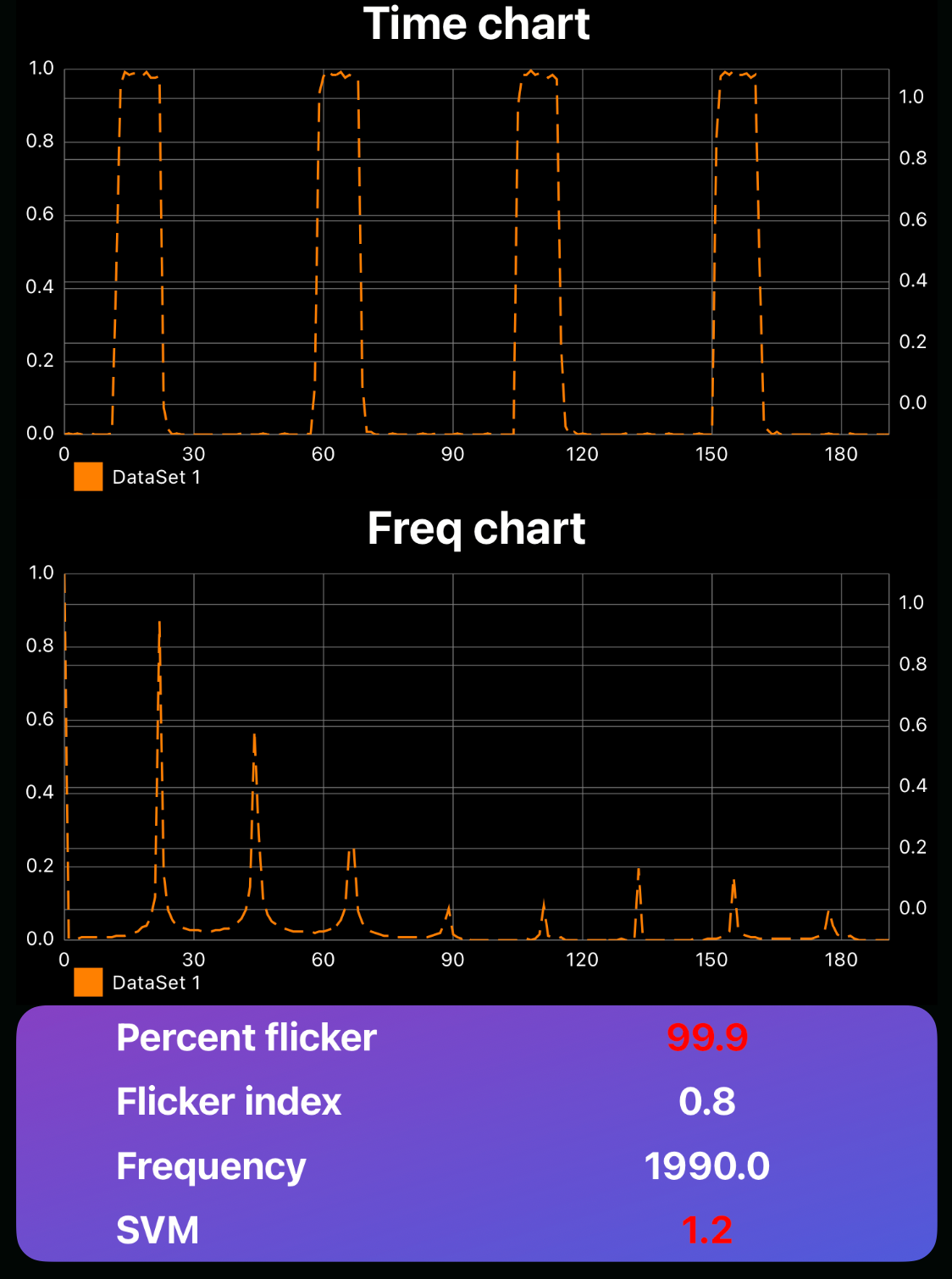

This is the one that I've been using. There are even better ones out there, but this also lets me conduct a full analysis of all the light power spectrum and frequencies. Here's an example of it's flicker measurement:

What About "Flicker Detection" Apps?

I tested several just to see if they had some type of tech that would let them work better than just taking a slow motion video. They didn't seem to be able to detect any flicker with a very high frequency, but they were at least capable of measuring modulation depth.

Here is one that seemed to work decently well.

Note: If you use one of these apps, make sure to put your phone on a tripod and aim the camera at a still, white piece of paper in front of the light. If you hold it in your hand then it can easily confuse hand motion with real flicker.

What About Your Computer Screen?

Most modern LED monitors flicker when dimmed using PWM backlight control. If you're sensitive to flicker:

- Use monitors that advertise "flicker-free" technology (usually DC dimming)

- Keep brightness at 100% and adjust with software (reduces PWM duty cycle issues)

- Use external color/brightness software like f.lux to avoid native PWM dimming

How to Shop for Flicker-Safe Lighting

Most bulb packaging doesn’t list flicker metrics, but you can still stack the odds in your favor.

1. Look for Clues in the Specs

- Mentions of “low flicker,” “flicker-free,” “flicker-safe” from reputable brands.

- Technical notes like “constant current driver”, “low ripple DC”, or “no PWM dimming”.

2. Prefer Better-Engineered Product Categories

- Integrated LED fixtures (from serious lighting brands) often have better drivers than ultra-cheap screw-in bulbs.

- Commercial/architectural lines tend to be engineered to meet stricter office/standards specs.

3. Avoid the Highest-Risk Categories

- Ultra-cheap “no name” LED bulbs and strips.

- USB-powered LED gadgets with unknown drivers.

- Any product that shows obvious banding in slow-mo video at multiple dimming levels.

WARNING:Most dedicated "flicker free" lighting carries a significant cost mark-up. See below for popular, low-cost brands that I've tested to have safe amounts of flicker even if they don't advertise themselves as such.

Specific Recommendations for Sensitive Individuals

- Avoid dimming entirely unless you know the driver/dimmer combo is flicker-free across the full range

- For critical spaces (home office, bedroom), invest in premium flicker-free fixtures

- Consider specialty FL-41 tinted glasses to filter problematic wavelength. Generic green glasses can help as well. I tested a bunch, and these do a great job of letting in ONLY green light. They're a bit too dard for everyday use though. .

- If replacing fluorescents, ensure new LEDs have better flicker specs than electronic-ballast fluorescents

- In workspaces, combine overhead ambient lighting (flicker-free) with task lighting (also flicker-free)

- The more distinct light sources you have in your space, the more the can serve to mitigate any existing flicker (e.g. two lights that flicker at 100% depth will often result in the room going between 100% light and 50%, rather than 0%)

What About Older Technologies?

- Incandescent/Halogen: Still available in some markets. Naturally low flicker (~10-20% at 120 Hz) due to thermal inertia. Good fallback option if you can't find quality LEDs.

- High-Frequency Electronic Fluorescents: If you already have these (post-2000 installations), they're often better than cheap LEDs. The flicker is essentially negligible (<1%).

Environment-Specific Strategies

- Prioritize flicker-free overhead lighting (this affects everyone's productivity)

- Combine ambient + task lighting to reduce screen glare without dimming

- Use software (f.lux, Windows Night Light) to shift screen color temperature instead of dimming

- If employer won't upgrade lighting, request accommodation under disability laws (migraines are protected)

- Replace high-use areas first (kitchen, living room, bathroom)

- In bedrooms, avoid any flicker—it can interfere with circadian rhythms and sleep quality

- Test before buying in bulk—get 1-2 samples and evaluate comfort over days

- This is critical. Children and patients are particularly vulnerable populations

- Specify IEEE 1789 compliance in procurement contracts

- Prioritize visual comfort over cost savings—flicker affects learning, behavior, and recovery

- Eliminate stroboscopic effect around rotating machinery (major safety hazard)

- Use very high-frequency (>2 kHz) or DC-driven LEDs

- This is where flicker-free isn't optional—it's life-or-death

Why This Matters: The Public Health Blindspot

The flicker problem represents a significant market failure. Here's why:

1. The Technology Exists

High-quality, flicker-free LED drivers using multi-stage conversion and constant current reduction (CCR) dimming are mature, proven technologies. They're used extensively in medical devices, studio lighting, and industrial applications.

2. The Science Is Clear

The link between flicker and health effects is extensively documented. IEEE 1789 provides clear, actionable standards. This isn't controversial or uncertain science.

3. The Problem Is Economic, Not Technical

Manufacturers prioritize minimizing component cost over health outcomes because:

- There are no binding regulations requiring flicker disclosure

- Consumer awareness is minimal

- The health costs (lost productivity, medical treatment) are externalized—not paid by the manufacturer

4. The Impact Is Widespread

This isn't a niche issue affecting a tiny population:

- General population: Cumulative effects on productivity, mood, wellbeing

- 12-15% with migraine: A potent, avoidable trigger for a debilitating neurological condition[9]

- Children in schools: Developing brains exposed 6-8 hours/day to suboptimal lighting

- Office workers: Baseline doubling of headache incidence is a massive productivity drain[1]

- Consumer demand: Informed buyers insisting on specifications

- Regulatory action: Making IEEE 1789 compliance mandatory, not optional

- Professional awareness: Architects, lighting designers, and facilities managers prioritizing health

Summary: Your Action Plan

The Problem

Many modern LEDs flicker 100-120 times per second with up to 100% modulation. This imperceptible strobing causes measurable neurological stress, resulting in headaches, eyestrain, and fatigue in the general population—and acting as a potent migraine trigger for the 12-15% of people who suffer from it.

The Mechanism

Your visual cortex processes flicker even when you can't consciously see it. In people with cortical hyperexcitability (migraineurs), this sensory overload activates pain pathways. In everyone else, it's a chronic energy drain on visual processing.

The Solution

Aim for:

- Frequency: ≥1,250 Hz (or essentially DC/constant)

- Modulation depth: ≤5-10%

- Look for: "Flicker-free," "IEEE 1789 compliant," or "DC driver" specifications

- Avoid: PWM dimming, cheap no-name LEDs, anything without published specs

Test Your Current Lighting

- Use the hand-wave test or smartphone slow-mo

- If you experience eyestrain or headaches under certain lights, trust your nervous system

- For critical spaces, invest in a flicker meter

For Migraineurs Specifically

- This is a legitimate, evidence-based environmental trigger

- Eliminating flicker in your primary environments may significantly reduce attack frequency

- Consider FL-41 tinted glasses as supplementary protection

- Advocate for accommodations in workplaces/schools—this is a documented disability issue

References

[1] Wilkins AJ, Veitch J, Lehman B. "LED lighting flicker and potential health concerns: IEEE standard PAR1789 update." IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (2010). Link

[2] IEEE Std 1789-2015. "IEEE Recommended Practices for Modulating Current in High-Brightness LEDs for Mitigating Health Risks to Viewers." Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (2015). Link

[3] Wilkins A, Nimmo-Smith I, Slater A, Bedocs L. "Fluorescent lighting, headaches and eyestrain." Lighting Research & Technology 21(1):11-18 (1989). Link

[4] Cucchiara B, Datta R, Aguirre GK, Idoko KE, Detre J. "Measurement of visual sensitivity in migraine: Validation of two scales and correlation with visual cortex activation." Cephalalgia 35(7):585-592 (2015). Link

[5] Shepherd AJ. "Detection and discrimination of flicker contrast in migraine." Cephalalgia 26(6):629-632 (2006). Link

[6] Coppola G, Di Renzo A, Petolicchio B, et al. "Aberrant interactions of cortical networks in chronic migraine: A resting-state fMRI study." Neurology 92(22):e2550-e2558 (2019). Link

[7] Puledda F, Ffytche D, Lythgoe DJ, O'Daly O, Williams SC, Goadsby PJ. "Imaging the Visual Network in the Migraine Spectrum." Frontiers in Neurology 10:1325 (2019). Link

[8] Cosentino G, Fierro B, Vigneri S, et al. "Effects of Visual Cortex Activation on the Nociceptive Blink Reflex in Healthy Subjects." Journal of Physiology 592(Pt 19):4357-4370 (2014). Link

[9] NHS Inform. "Migraine." National Health Service Scotland. Link

[10] Marcus DA, Soso MJ. "Migraine and stripe-induced visual discomfort." Archives of Neurology 46(10):1129-1132 (1989). Link

[11] Panayiotopoulos CP. "Reflex Seizures and Reflex Epilepsies." In: Epilepsy: A Comprehensive Textbook, 2nd edition. National Center for Biotechnology Information (2012). Link

[12] Jaadane I, Villalpando Rodriguez GE, Boulenguez P, et al. "Effects of white light-emitting diode (LED) exposure on retinal pigment epithelium in vivo." Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 21(12):3453-3466 (2017). Link

[13] Tan J, Miller NJ, Royer MP, Irvin L. "Temporal light modulation: A phantom array visibility measure." Lighting Research & Technology. 2024. Link

[14] Miller NJ, Irvin LC, Royer MP, Strachan CD. "Visibility and annoyance of the phantom array effect varies with age and history of migraine." Lighting Research & Technology. 2024;56(7):676–706. Link

[15] Park JC, Kim J, Shin J, et al. "Saccadic eye movement speed is related to variations in phantom array effect visibility." Scientific Reports. 2023;13:11109. Link

[16] International Energy Agency 4E SSL Annex. "Review of Health Effects of Temporal Light Modulation." IEA 4E Solid State Lighting Annex; 2024. Link

[17] Martinsons C, Kong X, Heynderickx I, Tengelin MN, Källberg S. “The Phantom Array Effect Explained Using Simple Formulas.” CIE Midterm Meeting 2025, Commission Internationale de l’Éclairage, Vienna, Austria (2025). Link